Biology professor introduces a new grading system labeled 'ungrading'

Carrie Olson-Manning, associate professor of biology, started using a grading system last fall that is focused on student growth through learning and feedback. The “ungrading” approach takes away pressure from students performing on exams and gives them a chance to learn from their mistakes.

“When you apply grades, students become less curious, they do more shallow thinking, and they focus on how quickly they can learn to get the best grade possible,” Olson-Manning said.

Olson-Manning said that she dedicates a lot of her time to students and tries her best to help them understand whatever they are working on.

“An exam is not a performance but just another learning opportunity,” she said.

In Olson-Manning’s classes, tests are not given points. She marks the test as complete or incomplete based on whether the student understood the question and answered it correctly.

If the answer was wrong, she will provide a comment, and the student must go back to correct the mistake and teach themselves the correct answer.

Olson-Manning said that she bases the final grade not just on tests but also on the grades she gives students for assignments and projects.

These are graded based on effort and improvement of understanding throughout the assignment rather than simply getting the right answer. Students are required to complete a certain number of assignments to get a certain number of points.

If the student earns 90% or above of the total points, they receive an A; between 80 and 90% corresponds to a B, and so on.

Ollie Langley Peterson, a junior computer science major, said that she thinks that more professors should try ungrading.

“I feel like I learn way more. This grading system takes the pressure off of one-time, high-stakes graded tests,” Langley Peterson said. “I think if other teachers adopted this system, they would see improved understanding in their students’ work.”

Olson-Manning said that she likes this type of grading because students think critically and search for solutions and risks, knowing they will not lose points if they make mistakes.

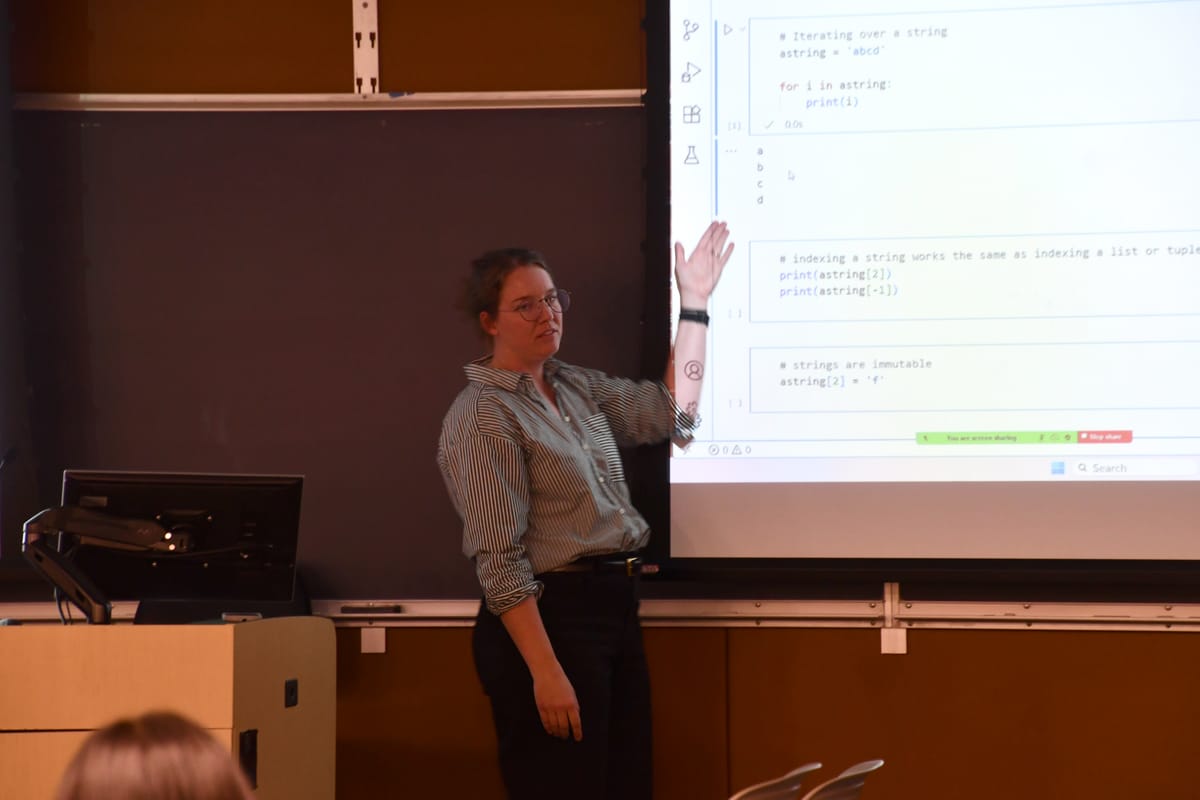

For example, in her computer science class, Olson-Manning assigns an independent project where students design and code their own game. They choose the type of game and must include visual elements, custom libraries and different coding techniques.

Throughout the semester, students submit drafts and receive feedback instead of losing points for mistakes. Projects are marked complete only after students address all comments.

Olson-Manning said that when she used to grade each draft, students did only the minimum to earn points. Now, with more creative control and no penalty for revising, they take bigger risks, show more pride in their work and end up learning much more.

Olson-Manning said that when tests, assignments and projects include points and comments, most students pay attention only to points and ignore the comments.

“What researchers have found is that if you put points and comments on tests, students don’t read the comments. So that way students need to read my feedback,” she said.

Olson-Manning uses this system only in classes that she teaches on her own, including Intro to Computer Science, Bioinformatics, and her Evolution class.

This system is not common at Augustana or other universities, but she believes it has real potential to change the way students think about learning. She also wishes that more professors would use it to help students grow and keep motivated to do their work.

Cami Fuglsby, assistant professor of computer science, said that she has never used this system but is willing to try.

“I do like the idea of not punishing students for their mistakes,” Fuglsby said.

The only thing Fuglsby is concerned about how time-consuming the system can be for professors. Providing feedback to every student takes almost twice as long as simply correcting their tests or assignments.

“This system takes pressure off students, but it adds pressure for professors, especially at the end of the semester,” Fuglsby said. “I am willing to try out this system in my smaller classes where I can give more individual attention, rather than large courses with many students.”

Olson-Manning first tried the system last year. She said she felt prepared to do so after reading the book “Ungrading: Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (and What to Do Instead),” edited by Susan D. Blum.

At the end of the year, Olson-Manning found that she was happy with the results but admitted there was room to improve. This year, she said she feels more confident using it.

Another student, junior Lexi Dilges, shared her positive experience with ungrading. After getting to know it, she noticed how more engaged she was and felt less stressed about it compared to other classes.

“At first I was nervous since I have never used a system like this before, but now I prefer it entirely to traditional grading,” Dilges said.

The system is still new and uncommon, but Olson-Manning and her students see the benefits. Students report feeling more engaged and curious as well as less stressed.

It will take time for other professors to get used to this system, but Olson-Manning hopes her success will inspire others to consider “ungrading” as a way to help students truly grow and learn.